By Duncan McGill

Transcript

Though shattered and currently in pieces, this was once a beautifully decorated Moustiers-produced Faience vessel. Its remnants were recovered from the site of Fort St. Pierre, a French fort in Mississippi. This vessel was in use in the early 18th century, when Fort St. Pierre was located in the French colony of La Louisiane. The fort and its soldiers held a valuable position along the Mississippi River. The artifact was likely a decorative piece, possibly owned by an officer or the commandant of the fort. French Faience as a form of decorative tin-glazed ceramics did not originate in France, but French ceramic factories produced faience by the 18th century.

The origin of the label “French Faience” actually comes from the principality of Faenza in Northern Italy. Whereas in Italy, Faience was known as majolica. The Italian Faience style was adopted by many European pottery makers, and to this day this refined earthenware is still created in France, Spain, Germany, and Scandinavia.

The production of Faience was inspired by the artistic qualities of imported Chinese porcelain. Chinese porcelain arrived in Europe through merchants from the Ottoman Empire, or later, via the Portuguese, once their seafaring explorers had established their own trade routes around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. The French adopted the Faience-style production from craftsmen in Northern Ital,y as the demand for the fine, high-quality porcelain increased. The most readily available French varieties of Faience included Marseilles Faience, which came from the southeastern province of Provence, France, bordering Italy. Many other manufactories were also built in French cities such as Moustiers, Nevers, and Rouen. The craftsmen of Strasbourg, near the French-German border, also created their own version of French Faience.

Due to the cultural significance and political importance of France in the 17th century, many other nations adopted the creation of faience-like earthenware, mimicking the qualities of the ceramic while adding their own cultural touches. For example, tin-glazed earthenware produced in Moorish Spain in the 17th century is known as Hispano-Moresque ware. The original Faenza producers of majolica in northern Italy inspired this style of faience. By the 18th century, German ceramic-makers in Nürnberg, Hanau, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Stockelsdorf produced French-inspired faience vessels.

The production of faience was deeply political. After the Protestant Reformation and the League Wars, Protestant Dutch, German, and English Delftware-makers competed with the Catholic version of faience produced in Spain, Italy, and France. This competition led to an increasing amount of nationalism attributed to the earthenware. The physical differences between the Protestant and Catholic faience vessels were quite stark. Catholic, mainly French, faience rarely was marked by the producer or advertised as a Catholic-produced piece of work. Instead, the quality of the craftsmanship acted as the advertisement for the producer. If there were indications of where pieces were produced, it was applied to the vessel by a glaze slip bearing the craftsmen’s signature in their particular style of work. This situation is quite contrary to the German and Protestant production of Faience. English Delftware, and Dutch and German producers marked their pieces with names, numbers, and dates of production. Many consumers thought this amounted to a lower level of quality, and would lead to standardization, which is exactly what happened.

The recurring theme of deeply political goods was not limited to pottery. The stigma of lower-quality German goods was applied to anything that came from a German-speaking nation. This affected the cultural and monetary value of the faience, as Protestant-produced faience dropped in price. In order to make up for the demand, the manufactories produced a higher volume of ceramic vessels. This situation led to a wide disparity in cultural and monetary value between Catholic- and Protestant-produced faience. Catholic goods were appreciated at a higher value due to their exceeding quality, compared to the common every-day usage and lower standards of production observed in the Protestant-produced earthenware. Though in reality the difference in quality level may not have been so dramatic, these national stereotypes were perceived as real by the wealthy investors of the New World colonies.

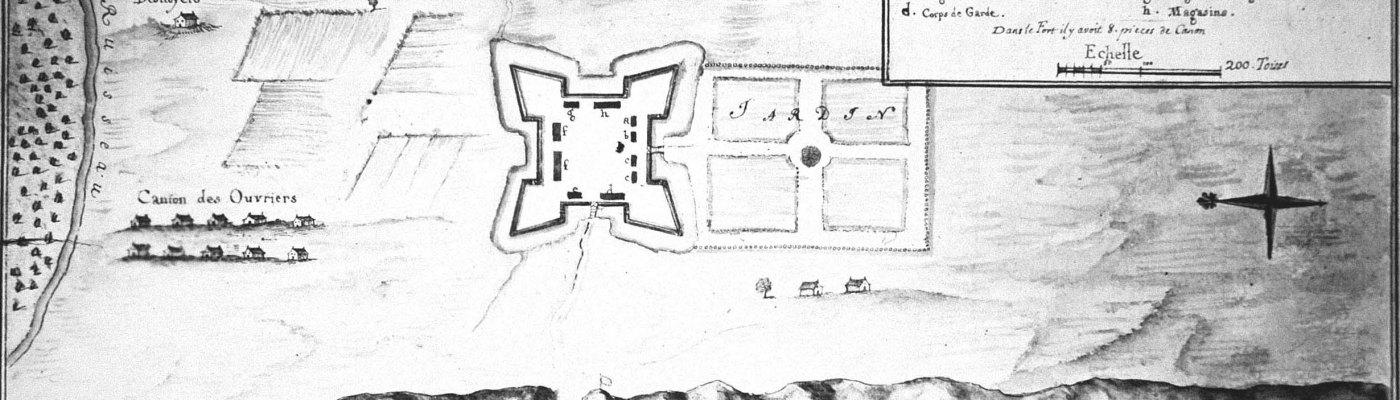

Some decorative faience vessels were fragile and expensive forms of earthenware that tried to mimic the qualities of Chinese porcelain. In colonial Louisiane, faience was shipped to the colony for use as an everyday serving ware. In fact, sometimes production rejects and decoration mistakes were shipped to the colony of Louisiane, as the French living there only had access to shipped goods. In addition to plates, bowls, and serving platters, faience formed apothecary jars, drinking cups, beer steins, jugs, and pitchers. Excavations at Fort St. Pierre uncovered faience ceramic fragments with a variety of decorative patterns, indicating that soldiers at this outpost had some access to goods from France.

The Faience uncovered in the excavations of Fort Saint Pierre were not the fine-quality porcelain that marked the height of European pottery manufacture. Rather, the colonies tended to get the mistakes, and the extra inventory that overproduction left unsold. The basic and easily reproduced patterns in only a single color mark the difference between the ‘excess’ and the high-quality porcelain. The superior products would have more intricate designs with multiple colored glazes, and have the look of one-of-a-kind, rather than mass-produced designs. Most of the fragments from Fort St. Pierre were plain white, or had designs in blue paint. A few fragments were white with yellow paint, and one vessel was apparently highly decorated with several colors. For the folks who last owned these fragments, these vessels were likely everyday dishes for serving or eating.

Bibliography

Avery, George E. French Colonial Pottery : an International Conference. Natchitoches, La.: Northwestern State University Press, 2007.

Louisiana as a French Colony – Louisiana: European Explorations and the Louisiana Purchase.” The Library of Congress.

Malischke, Lisamarie. Heterogeneity of Early French and Native Forts, Settlements, and Villages: A Comparison to Fort St. Pierre (1719-1729) In French Colonial Louisiane. 2015.

Métreau, Laetitia, and Jean Rosen. Origin and Development of French Faience: The

Contribution of Archaeology and the Physical Sciences.